BUILDING A MAN: THE MASONRY OF RUDYARD KIPLING’S “IF”

By Worshipful Brother Daniel Rivera

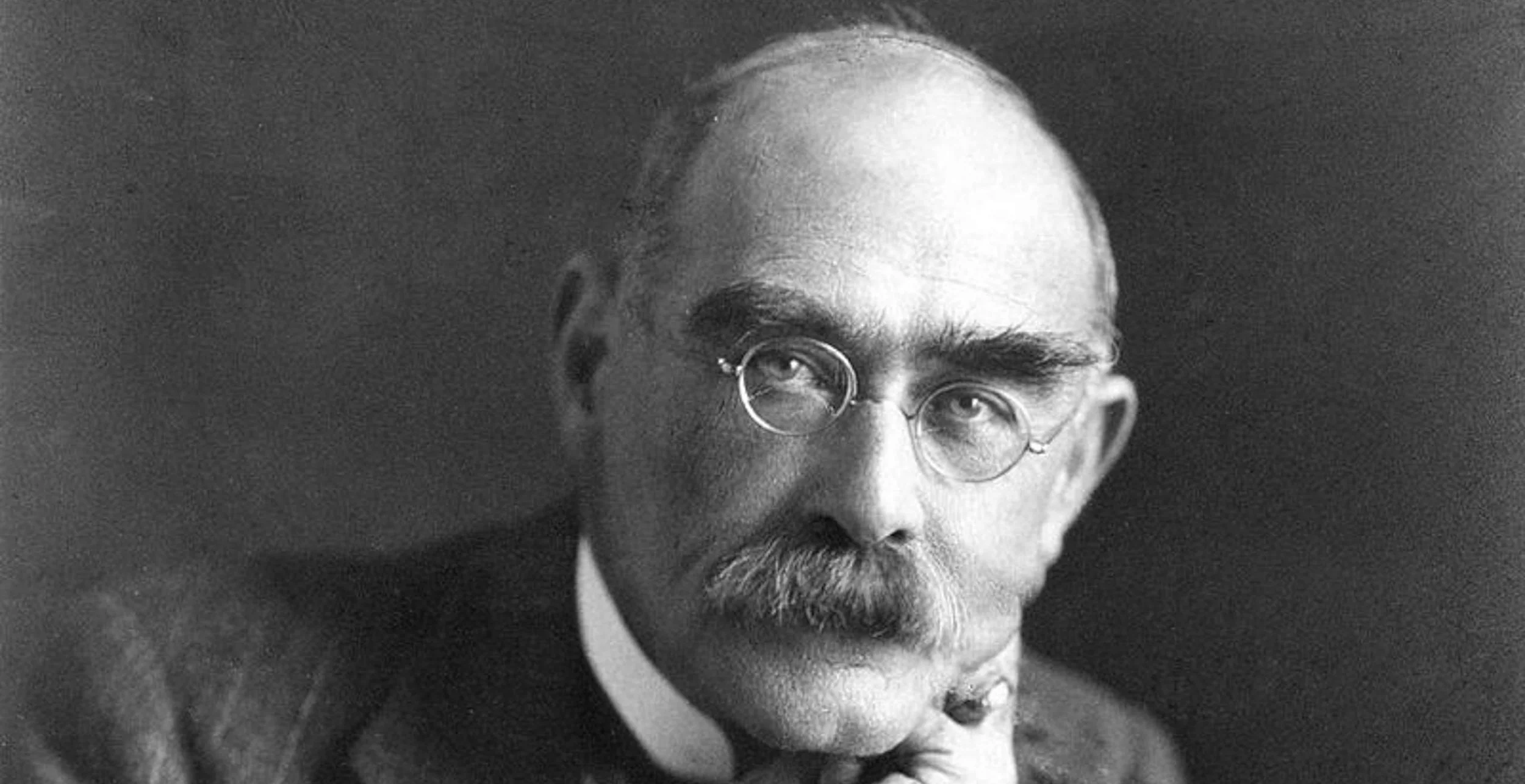

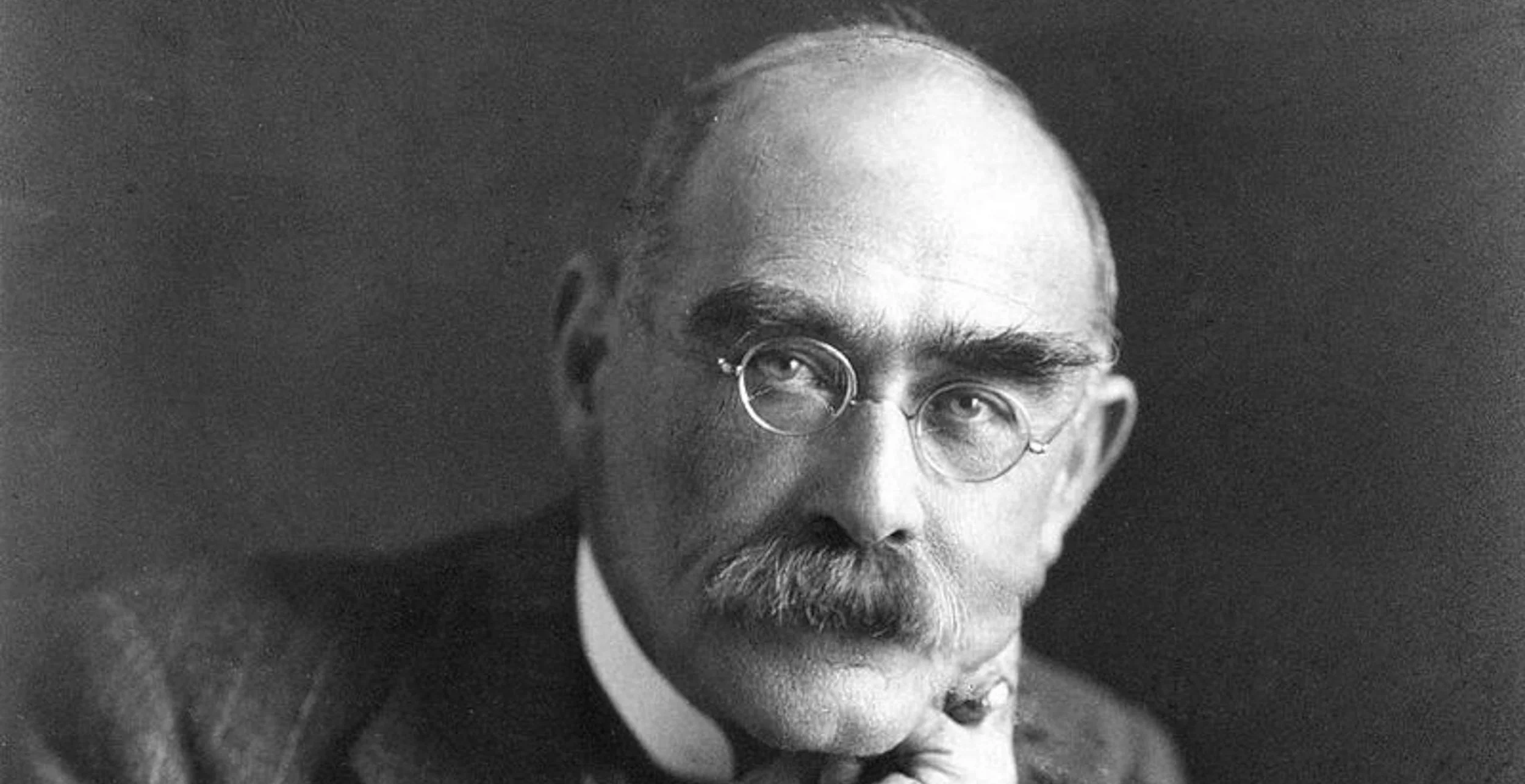

Rudyard Kipling’s poem If has long been cherished as a father’s counsel to his son, a secular catechism of character. Yet when read in light of Kipling’s own Masonic life, it also seems an informal Masonic charge cast into verse. Bro. Kipling was initiated in Hope and Perseverance Lodge No. 782 at Lahore in 1886, at the age of twenty, and soon served as lodge secretary. In later recollections he emphasized that this lodge brought together Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and Christians on the level, an experience of spiritual and social universality that marked him deeply. In that context, If can be read as a poetic summation of the virtues the Craft seeks to cultivate: a man whose passions are governed, intellect disciplined, and will consecrated to duty.

Kipling’s own account of Hope and Perseverance Lodge is revealing. Writing of his Masonic career, he remembered: “I was entered by a member of the Brahmo Samaj (a Hindu), passed by a Mohammedan, and raised by an Englishman. Our Tyler was an Indian Jew.” This brief catalogue of creeds underscores the ideal of equality symbolized by the Level: whatever their religion or race, men met within the lodge as brethren. Such an environment lends resonance to the closing stanza of If, with its demand that the ideal man should be able to “talk with crowds and keep your virtue, / Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch.” The poem’s universal humanism—the insistence that all men “count with you, but none too much”—mirrors precisely that Masonic aspiration to respect every person while remaining inwardly free.

Structurally, the poem is a single extended conditional sentence: a litany of “ifs” followed by one great “then:” “you’ll be a Man, my son!” Many traditional Masonic addresses follow a similar pattern, enumerating conditions of conduct and concluding with the promise that, if fulfilled, the initiate will be a just and upright Mason. Freemasonry’s three primary degrees—Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master Mason each emphasize a different aspect of this formation: the Apprentice is taught to subdue his passions, the Fellowcraft to cultivate his intellect, and the Master Mason to perfect his moral will in the face of loss and death. Read through that lens, the four stanzas of If trace a movement from emotional mastery, through disciplined thought, to persevering will, and finally to the integrated character of the Perfect Ashlar, the fully worked stone ready to be set in the spiritual temple.

The first stanza aligns closely with the teaching of the Entered Apprentice. “If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs and blaming it on you” parallels the Apprentice’s instruction to govern his passions. The young Mason is admonished to be calm, truthful, and charitable in his judgments, whatever provocations he faces. When Kipling adds, “If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, / But make allowance for their doubting too,” he captures two complementary Masonic virtues: a prudent confidence in one’s duty, and a charitable understanding of others’ limitations. The working tools associated with the Fellowcraft —the Plumb and Square —symbolize acting honestly and walking uprightly; the stanza’s refusal to “deal in lies” or “give way to hating,” coupled with its warning not to “look too good, nor talk too wise,” embodies that square, modest rectitude. The poem’s first movement, then, corresponds to the rough shaping of the stone: the candidate begins by learning restraint, humility, and charity.

The second stanza continues in Fellowcraft territory, emphasizing intellect, balance, and the work of building. “If you can dream—and not make dreams your master; / If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim” addresses the temptation to idolize imagination or abstract reason. The lodge encourages the study of the liberal arts and sciences, but always under the guidance of the Volume of the Sacred Law, reminding the Craftsman that his thinking must be squared by morality and reverence. The famous lines, “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same,” echo the symbolism of the Level, which teaches the Mason to regard success and failure as passing states that must not unseat his constancy. Masonic writers often stress that the true work of the Craft is the continuous building of a moral and spiritual temple within the heart; Kipling’s image of seeing “the things you gave your life to, broken,” and then stooping “and build ’em up with worn-out tools,” is a perfect allegory of that labor. External projects may fail, reputations may be ruined, but the Fellowcraft returns to his work with such tools as he has, continuing to shape himself and his world.

The third stanza of If deepens the theme of detachment and perseverance, in a way that resonates strikingly with the Master Mason degree. The Master Mason has faced, in allegorical form, the loss of everything, including life itself, in the drama of Hiram Abiff. In that light, Kipling’s counsel to “make one heap of all your winnings / And risk it on one turn of pitch-and- toss,” then to lose and “never breathe a word about your loss,” captures the Mason’s ideal of freedom from enslavement to fortune. The true treasure is character, not “winnings.” More powerful still is the stanza’s climactic image: “If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew / To serve your turn long after they are gone… / Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’” Here the poem approaches the inner core of Masonic self-mastery. The Compasses, which teach the Mason to circumscribe and keep his passions within due bounds, also encircle a central point: the moral will aligned with the Good. When human strength and wisdom fail, it is that inward point, the persevering will prayerfully directed to Deity, that commands the outer life to endure. Quiet patience and persevering fortitude overcome all obstacles.

The final stanza portrays the man who has traversed all these stages. He is able to “talk with crowds and keep [his] virtue,” or “walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch.” This is the Level fully lived: external rank neither inflates him nor intimidates him. He allows “all men” to count with him, “but none too much,” an elegant summary of the virtue of Justice as Masonry understands it: every person’s dignity and claim is recognized, yet the Mason remains bound above all to conscience, not to party or clique. The closing image, filling “the unforgiving minute / With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run”—naturally recalls the Apprentice’s 24–inch Gauge, with its lesson on dividing the day among service to God, duty to neighbor, and rest. Time is unforgiving because it cannot be reclaimed; to give each minute its full “distance” is to allocate one’s life according to that moral measure, leaving no hour idle or wasted. When Kipling finally declares that fulfilling all these “ifs” will make his son a “Man,” he is not merely promising biological adulthood or social success. He is describing the same mature, integrated person that Masonic lectures call the “just and upright Mason,” a perfected stone of the inner temple.

Kipling never officially labelled If a Masonic poem, and it stands perfectly well as a universal meditation on manhood. Literary critics have often compared it to Stoic moral teaching: a Victorian echo of Hellenistic ethics, emphasizing self-control, endurance, and indifference to external fortune. But that Stoic note does not conflict with a Masonic reading; rather, it shows that Freemasonry taps into a broader classical and biblical tradition of virtue ethics. In the light of Kipling’s own lodge experience, If can be heard as a poetic charge to any young man—son or initiate—who asks what kind of person he ought to become. Its vision of a man who governs his passions, disciplines his mind, consecrates his will, and walks among humble crowds and powerful kings on the same Level. It is, in essence, the vision of manhood that the Masonic Fraternity has always and will always aim to craft.

*DANIEL RIVERA is Past Master (2025) of Reseda No. 666 and a Past Master of Southern California Research Lodge (2023-2024), in Los Angeles, California. He continues to serve in the editorial and executive teams of the award-winning “Fraternal Review” magazine. *